The general public and the media usually pay scant attention to the Summit of the Americas, perhaps because the process tends to be detached from the citizens’ daily worries and there is little understanding about it. This time, however, will be different. The 2015 Summit of the Americas in Panama on April 10–11 will not pass unnoticed because it will witness a historic moment in inter-American relations: the return of Cuba to a hemispheric forum, taking a seat alongside the United States.

Beyond its official theme—“Prosperity with Equity: The Challenge of Cooperation in the Americas”—the truly important thing about this gathering is that for the first time the whole region will be included. This is the result of at least two processes. On the one hand, the increasing pressure exercised by the Latin American countries in this regard; and, on the other hand, Washington’s decision to initiate a path of normalization of its bilateral relations with Cuba. The former must have contributed to the latter, since in the last ten years the Cuban issue has proved to be incrementally divisive and rarefied the political atmosphere in the continent. In fact, it was central to the “challenge to cooperation in the Americas,” noted in the summit’s title. So how did the seminal decision of inviting Cuba come about? It is worth analyzing the period leading up to the summit because it reflects more general trends in regional governance.

The Return of Cuba

Cuba’s participation in the Summit of the Americas can be seen as an additional—and crucial—step in a longer process of reintegrating the country into regional schemes. Indeed, the twenty-first century has seen a rise of Latin American multilateralism whereby these countries created a number of new regional associations with the purpose of promoting political dialogue and intergovernmental cooperation on a vast array of issues, ranging from education to infrastructure building and transparency in defense spending. Cuba rode this wave of regionalism. In 2004 it first participated with Venezuela as a founding member of ALBA (Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas). Then in 2008 it joined the Rio Group—a multilateral entity created in 1986 with the aim of producing “Latin American solutions to Latin American problems”—twenty-two years after its inception. Finally, Cuba was not only present at the launching of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC)—a bloc created as the successor to the Rio Group, notably excluding the United States and Canada—in 2010–2011 but it also obtained the pro tempore presidency: For a whole year Cuban diplomats represented and spoke on behalf of Latin America in multilateral forums and other international venues. The presence of thirty-three heads of state at CELAC’s second summit held last year in Havana was the culmination of this process. It symbolized a consensus spanning the region from the Rio Bravo (known in the United States as Rio Grande) to its southern tip and sent a strong message: Beyond existing differences or affinities with the island, Cuba should be granted a place at the table.

No doubt this was partly the result of a change in the region’s political climate brought about by the so-called left turn in Latin America coupled with a perceived relative decline of U.S. regional hegemony, particularly in South America. The creation of ALBA and CELAC (but also the Union of South American Nations, known as UNASUR) was inspired—among other things—by the goal of asserting autonomy vis-à-vis the United States. Cuban membership in those groups, in fact, works as a symbol of these autonomist or anti-hegemonic pretenses; a symbol that some countries decided to push further by demanding that Cuba be included also in the institutional spaces created and sponsored by the United States to engage with the rest of the region, that is, the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Summit of the Americas.

The “Cubanization” of the Inter-American Agenda

Indeed, during the Fifth Summit of the Americas held in Trinidad and Tobago in 2009, several presidents called for an end to the exclusion of Cuba from the summit process and the OAS. The host country’s prime minister stated: “There was a clear consensus that the reintegration of Cuba in the inter-American relations is an essential step toward the building of a more cohesive and integrated Americas.” Even if the recently elected U.S. President Barack Obama aroused sympathies and promised to launch a new and more positive era of relations with Latin America, he could not escape from listening to recriminations regarding the Cuban embargo and the island’s absence in that and other venues.

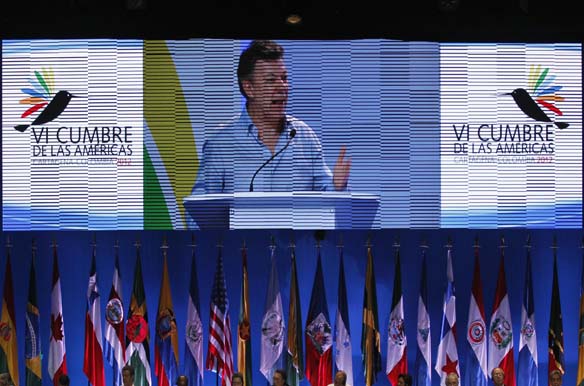

As pressure mounted, it was decided to take the Cuban issue to the OAS General Assembly. The Permanent Council—a political body of the OAS, composed of the permanent representatives of the member states—created a working group in charge of drafting a resolution on the topic. After a very difficult and strained process of negotiations, in June 2009 the thirty-ninth OAS General Assembly gathered in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, and adopted a resolution that annulled the 1962 decision excluding Cuba from participation in the inter-American system. But this was not the end of the matter. Three years later, the Sixth Summit of the Americas in Cartagena, Colombia, was again dominated by the Cuban question, to the point that no final declaration was issued due to lack of consensus: In particular the United States and Canada refused to sign a document that called for inviting Cuba to the next gathering. Ecuador and Nicaragua did not attend that summit, citing their solidarity with Cuba, whereas the presidents of Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, and Colombia eloquently called for including the island in this hemispheric forum. The ALBA countries also announced their decision not to take part in future Summits of the Americas without the presence of Cuba. If anything, Cartagena showed that Anglo and Latin America were sharply divided over what to do with Havana. That element alone tainted the whole summit process.

Contesting U.S.-Led Multilateralism

One might think that at least some Latin American countries are engaging in a more general strategy of “contested multilateralism.” As Julia Morse and Robert Keohane explain, this happens when “states are dissatisfied with existing institutions” and they “decide that it is worthwhile either to shift their focus to other institutions or to create new ones.” Clearly, ALBA countries—relying on the ambivalent positions of other important nations such as Brazil and Argentina—are expressing their unhappiness with hemispheric forums that they perceive as vehicles for projecting U.S. hegemony (its power and values) throughout the Americas. This is why they are constantly contesting the OAS and the Summit of the Americas’ procedures, goals, and, ultimately, existence. They try to weaken them financially and politically, continuously threatening their non-participation or even their exit. And the presence of new Latin American regional associations in turn makes the threat more credible than before. In this framework, boycotting the summit on the grounds of Cuba’s exclusion was above all a great tactic to weaken the inter-American multilateral architecture.

In fact, after the Panamanian government formally invited Cuba in September 2014, Washington was put for a moment against a wall: If the Obama administration decided not to attend, it would mean the demise of the summit process; if, on the contrary, the United States did participate, but openly objected to Cuba’s presence, it would pay the price of humiliation for not being able to block it. But the December 17, 2014, announcement of a normalization route in the bilateral relations between the two countries was a game changer. Cuban presence in the summit can now be portrayed as a part and parcel of a jointly agreed process of rapprochement and not as a hassle for the United States. Looking at the big picture, one might argue that Cuban membership in fact strengthens the summit process as it tends to contradict the strategy of “contested multilateralism.” This can only be in Washington’s best interest.

What Would Make the Panama Summit a Success?

Although the Latin American political landscape is showing signs of change, at present there is little convergence between the United States and an important portion of Latin American countries. Therefore, true solutions to the hemisphere’s collective problems—such as the economic slowdown, transnational organized crime, and drug-related violence—are not really to be expected. There is, indeed, a multi-thematic agenda tailored to satisfy all countries; however, the truth is that this summit will not be about topics but about the attending personalities. Of course, the Venezuelan crisis will loom large and now Obama will take the heat for the imprudent policy of sanctions against President Nicolas Maduro government officials casted in the hyperbolic legal language of a “national security threat.”

With that in mind, the summit should be considered successful if:

- both President Obama and President Castro take part, shake hands, and appear together in a historic picture;

- the country delegations are able to agree on the contents and language of a final declaration—something that has been elusive in the last two occasions;

- there are few empty seats, aside (most likely) from that of Venezuelan president Maduro;

- and the Hemispheric Forum—part of the summit process that promotes the inclusion of civil society, including pro- and anti-Castro groups, in addressing issues on the agenda—and the separate and parallel, so-called "People’s Summit"—a gathering summoned by leftist unions and social movements to protest the summit—go smoothly, exchanging their disagreements, and showing dissent only at the rhetorical level.

The inter-American system can only survive if Washington pays heed to Latin American concerns and signals its understanding that there is a more leveled playing field in the region. The normalization process with Cuba is one such signal and, therefore, the Panama Summit might well prove to be a respite for the withered inter-American ideal.