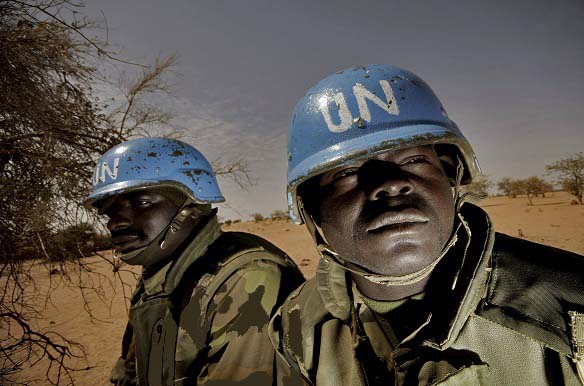

As threats to international peace and security continuously evolve, UN peacekeeping has proven a highly adaptable tool. Extensively used by the UN Security Council, peacekeeping operations address a wide range of policy challenges, from the more traditional monitoring of the tense maritime borders between Israel and Lebanon to conducting robust military operations against armed rebel groups threatening the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Global UN peacekeeping operations are large-scale by any standards: there are currently sixteen missions in place, involving almost 124,000 personnel from 122 countries—in an enterprise that costs $8.27 billion. The transformation of the instrument since it was first put in place in the late 1940s is tremendous. In the last decade the UN’s position on the field has become more complicated, notably since the 2004 attack on its headquarters in Baghdad, as the organization frequently sees itself as a party and a target in conflicts. Currently, UN missions are often stationed in fortified compounds, which have, in many places, decreased their capacity to establish popular legitimacy through direct interaction with the population.

Threats and Challenges to Peacekeeping

UN operations regularly take place in areas where there is endemic violence. In these contexts, missions have struggled to respond to the difficult challenge of protecting civilians in conditions where violations of humanitarian law, including sexual violence, are considered an instrument of warfare. The recurrent and increasingly frequent attacks on blue helmets further complicate their strategic position on the ground. In recent years, terrorist tactics in asymmetrical warfare have transformed the reality of UN peace operations, notably in the Golan Heights, Mali, and Somalia. The high expectations created by mandates to protect civilians have not been matched by institutional and military capacity, with considerable gaps between resolutions and actual deployment, and the insufficient provision of human and material resources to accomplish the mission.

In spite of these difficulties, UN peacekeeping remains the most important and legitimate tool the Security Council has to address threats to international peace and security. For this reason, in October 2014, Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon requested a comprehensive policy review of UN peace operations. Jose Ramos Horta, the former president of East Timor, a Nobel laureate, and then the secretary-general’s Special Representative in Guinea Bissau, was appointed to lead the panel. The mandate was broad: from the reconsideration of managerial and administrative arrangements to an evaluation of the changing nature of conflict and global challenges to peacebuilding.

By UN standards, the report published in June 2015 could be considered subtly subversive. Panel members did not limit themselves to technical or administrative matters (also in need of improvements), but were also critical of the way the Security Council mandates and equips its missions. By emphasizing the wide gap between the ambition of mandates and resources provided, the panel suggested a certain irresponsibility of the council toward the military forces it sends into crisis areas, and toward the civilians who must count on them for the protection of their lives. The central problem, it argued, is that mandates often lack focus, appropriate resources for implementation, and, importantly, a political strategy to eventually terminate the mission.

The Ramos Horta report is comprehensive and includes over one hundred specific recommendations to improve the planning, administration, and actual conduct of UN peace operations. Yet, as the report is evaluated by the different UN bodies in the upcoming General Assembly (GA) meetings, three main issues are likely to dominate discussions.

Improving Accountability

Over the last few years, it became abundantly clear that sexual exploitation and abuse is an endemic problem in UN-authorized peace operations—as it is in many military cultures worldwide. Even when UN operations are considered relatively effective, like in Haiti or Liberia, peacekeepers have continued to commit abuse against those they are supposed to protect, significantly harming the work and reputation of the United Nations. In the highly anarchic environments in which these operations take place, where impunity is seen as standard, it is indispensable to enhance the accountability of UN peacekeepers committing crimes.

The problem of holding troops accountable for wrongdoings goes beyond cases of sexual abuse. In general, the United Nations is largely unable to directly influence the disciplining of troops, which remains the responsibility of contributing states. It is still the case that UN member states refuse to allow their soldiers to be prosecuted by any UN panel or body, leaving all significant disciplinary or criminal proceedings to national militaries alone. Seldom, however, do national militaries prosecute soldiers for misdeeds allegedly committed under UN assignment. Improving global mechanisms of accountability, including the establishment of a black list of contributing states with recurrent human rights violations, will be a central topic of discussion in the coming month.

Bringing Politics Back Into Peacekeeping

The principal argument articulated in the Ramos Horta report is that UN Peace Operations must be subordinated to diplomatic strategies that can effectively address the (inherently political) questions underlying conflicts. Peacekeeping missions, like targeted sanctions and other instruments, tend to be more effective when subordinated to vibrant political activity. If not, they are likely to become ends in themselves and a part of the conflict landscape instead of a potential solution to it.

The increasingly important role of special representatives of the UN Secretary General and mission leaders is likely to be a central theme of discussions at upcoming UN meetings. These actors, when effective, are able to leverage their mediation capacity by coordinating UN agencies on the ground, as well as linking their work with that of neighboring states, regional organizations, and donors. This has proven critical to resolving political crises in the past. In addition, as centralized coordinators of political operations, they provide useful information and suggestions to the Security Council. Thus, the UN should strengthen its capacity to mediate conflicts, including through the negotiation with extremist armed groups. As the humanitarian sector has long recognized, negotiating does not necessarily confer legitimacy or recognition. If the Ramos Horta report is to be taken seriously by the Security Council, it must discuss ways to make missions more politically effective through the improved coordination of policy instruments (including diplomatic pressure) under the coordination of a strong mediation team.

More Fair and Effective Deployment

UN peace operations continue to suffer from the lack of human and material resources, especially those immediately available for deployment. While a standing military for the United Nations has long been held to be politically impossible, the Ramos Horta report provided useful alternatives for consideration. It recommend a new system of vanguard troops to be placed in areas with large numbers of conflicts, allowing the UN to quickly respond to imminent crises or unexpected escalations. Possible improvements also include the enhancement of so-called enabling units, those which take care of logistical challenges that make military bases work effectively.

UN peace operations remain deeply stratified. Poor countries continue to contribute the bulk of military personnel, who are often, unfortunately, also poorly trained and equipped. Wealthy countries, on the other hand, gradually abandoned UN operations during the 1990s, contributing mainly through their financial contributions. While specialized training centers have improved the qualification of troops in recent years, it is still necessary to ensure the return of wealthier, better trained and equipped militaries to the ground. It is particularly important that Security Council permanent members, those chiefly responsible for international peace and security, carry the burden corresponding to their privileges in the organization. If successful, this measure will contribute to improving the overall quality of operations as well as to providing new sets of resources to the command and control structure of peacekeeping operations.

Practical Recommendations

The seventieth General Assembly will be a critical opportunity for member states to review the progress and consider the remaining challenges of UN peace operations in the past decade. The UN Peacekeeping Summit, a high-profile event hosted by President Barack Obama on the margins of the GA, will serve as an opportunity for many to demonstrate support to peacekeeping and increase their own contributions to the system.

In doing so, participants should focus on improving the quantity, quality, and speed of deployments, working to improve the pace of response as well as the balance of contributions among member states. Better coordination by the Security Council on its wide range of policy instruments, under the direction of political mediators, should also be a center of discussions. To ensure greater consistency in the quality of leadership, it is important to move away from a selection process driven by political motivations and toward the establishment of a merit-based system, with improved training and greater coordination authority to those in charge of political processes. Finally, following effective sanctions practice, the Security Council should consider the establishment of independent panels of experts to monitor and suggest improvements on each peacekeeping operation deployed. They should be tasked with monitoring the fulfilment of the mandate, the collaboration of host and neighboring states, and, whenever relevant, investigate abuses and unintended consequences of UN military action. This will embed a learning process in peace operations that will contribute to the task of those in charge of improving mandates and operations on a permanent basis.