The November 2024 U.S. presidential election will have serious implications for the world. In the second of a five-part series, this global perspectives roundup features four reflections on why the U.S. election outcome matters for the Indo-Pacific.

Southeast Asia’s High Economic and Security Stakes in the U.S. Elections

Few elections draw global attention like the U.S. presidential race. For Southeast Asia and the wider Indo-Pacific, a Donald Trump 2.0 administration could signal a return to his America First policies, likely bringing more protectionist trade measures and a shift in regional security dynamics. A Kamala Harris win, on the other hand, could reaffirm the United States’ commitment to multilateralism, emphasizing trade, economic development, and climate change cooperation. Thus, the 2024 U.S. presidential election carries profound implications for the region’s geopolitical and economic landscape, particularly in terms of trade, security partnerships, and diplomatic ties with Washington.

In an increasingly uncertain global environment, the United States’ engagement with the Indo-Pacific remains crucial. As vice president, Harris has been active in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and East Asian summits, solidifying U.S. commitments to peace, stability, and prosperity in the region. A Harris presidency would likely see continued U.S. participation in ASEAN-led frameworks like the ASEAN Summit, East Asia Summit, ASEAN Regional Forum, ASEAN Defence Ministerial Meetings Plus, and multilateral agreements such as the QUAD (the informal security dialogue among the United States, Australia, India, and Japan) and AUKUS (the trilateral security among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States), demonstrating and reinforcing the United States as a reliable partner. For U.S. defense allies like the Philippines, active U.S. involvement could further strengthen ties, especially as tensions with China over the South China Sea escalate. At the same time, a Harris presidency would also enhance cooperation in nontraditional security issues like climate security, humanitarian assistance, cybersecurity and health security.

A Trump presidency, however, could introduce greater uncertainty. As an isolationist, Trump could scale back security support and military presence, raising concerns across the region. His return could also intensify the U.S.-China rivalry, forcing Southeast Asian nations—who prefer neutrality—to face tougher choices, potentially undermining ASEAN’s strategic autonomy and centrality.

The economic stakes are equally high. A Trump-led shift to even greater protectionist trade policies could severely impact Indo-Pacific economies. His proposed 10 percent tariffs on all imports and threat of a 60 percent tariff hike on Chinese goods would raise export costs and destabilise supply chains, particularly because many regional economies are tied to China. This would drive up production costs across the Indo-Pacific.

In contrast, a Harris administration could pursue deeper multilateral engagement such as advancing the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) to counterbalance China’s influence, though trade negotiations could still be drawn out. Trump’s threat to abandon IPEF, as he did with the Trans-Pacific Partnership, could further unsettle the region’s economic dynamics and erode trust in the United States as an economic partner.

U.S. Election Will Have an Important Impact on China-U.S. Relations

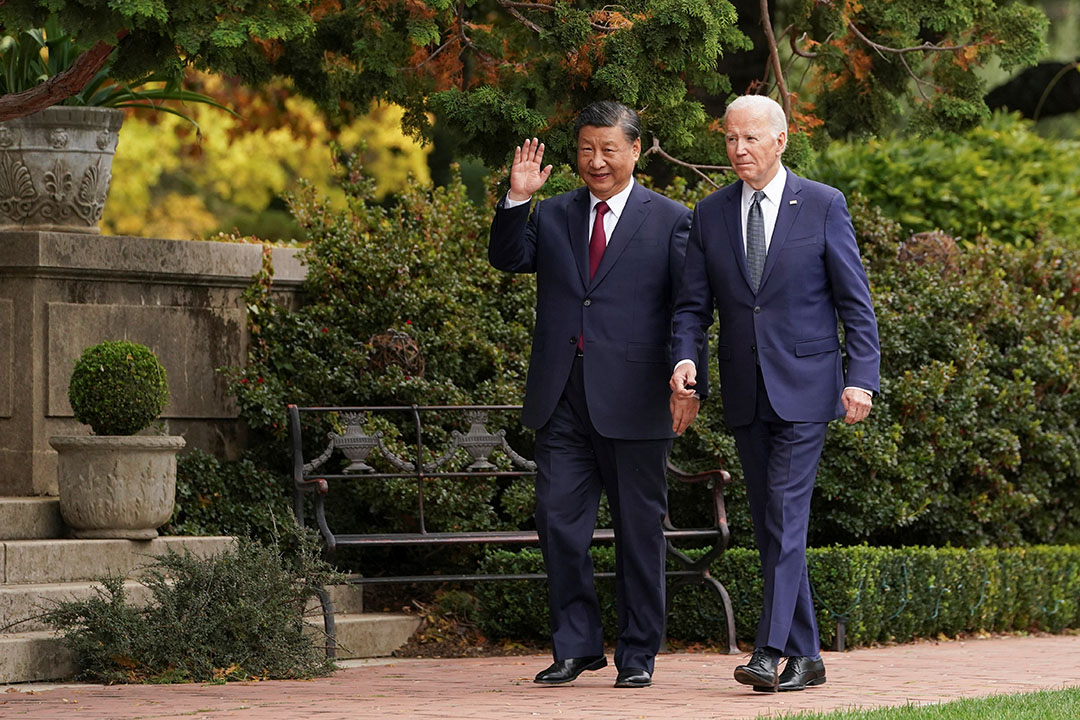

Countries in the Indo-Pacific region are highly concerned about the outcome of the U.S. presidential election. This vote will have a significant impact on the security and economic development of the region, and, in particular, will affect the development of the region’s most important bilateral relationship, between China and the United States, over the next four years.

Most Chinese researchers believe that the U.S. grand strategy toward China—containing China’s space for development to prevent it from challenging U.S. hegemony—has become the consensus of the Democratic and Republican parties, as well as the consensus of Congress and the executive branch. Regardless of who wins the presidency and controls Congress, the general direction of the next U.S. administration’s policy toward China seems all but certain. Despite this, the region is paying close attention to the outcome of these elections as they will have several concrete impacts on China-U.S. relations.

First, the policy teams that both former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris could select to shape their administrations’ postures on China-U.S. relations will be significant. While Trump’s views on China are widely known, we know less about Harris’s views. Her China policy team is likely to be composed of personnel from the Barack Obama and Joe Biden administrations, while Trump’s China policy team is likely to include several “super hawks” on China.

Second, the policy priorities of Trump and Harris matter. Trump’s focus is undoubtedly on the economic and trade relationship between the two countries, and his rhetoric about imposing 60 percent tariffs on Chinese goods and eliminating China’s most-favored-nation (MFN) status for trade would truly decouple the economies of the two countries if it were translated into actual policy. So far, Harris has not given a comprehensive account of her foreign policy agenda, but we can anticipate a continuation of the Biden administration’s China policy, which places more emphasis on scientific and technological competition with China than on economic and trade relations. Differences in U.S. policy priorities affect China’s policy responses, for example, its agenda-setting, resource allocation, and domestic policy adjustments to the bilateral relationship, and, in turn, the future of the bilateral relationship.

Third, the political styles of a Trump or Harris administration are important. Trump has surrounded himself with super hawks that show a great distain for the Chinese Communist Party that is reflected in their communication style and word choices. Harris, if she continues Biden’s style, will likely be relatively restrained on this issue.

Therefore, it is not enough to generalize Trump’s and Harris’ policies toward China by saying that the difference between them is only bad and worse. A more nuanced analysis of the impact of the candidates’ policies on all areas of China-U.S. relations is needed now more than ever.

Indo-Pacific Eyes Are on Washington and the Future of Alliances

Officials in Indo-Pacific capitals are watching the U.S. presidential election intently. They are particularly interested in three questions: What is the next president’s worldview? How will the next president approach China? And how will the next president treat the United States’ allies in the region?

On the first question, Donald Trump defines the United States’ interests much more narrowly than does Kamala Harris.

If Trump isn’t an isolationist, he is certainly iso-curious. He does not believe in the mainstream tradition of U.S. leadership. As he once said: “I’m the president of the United States—I’m not the president of the globe.” Kamala Harris has a different view. At the Democratic National Convention in August, she pledged to ensure “that America, not China, wins the competition for the twenty-first century, and that we strengthen, not abdicate, our global leadership.”

Trump is also hostile to free trade. He has promised tariffs of 10 percent or even 20 percent on all imports to the United States, and even higher tariffs on Chinese imports. At the debate, Trump claimed that “other countries are going to finally, after 75 years, pay us back for all that we’ve done for the world.” While Harris is more pro-trade than Trump, that isn’t saying much. She has previously criticised or voted against free trade agreements, and her campaign has pledged to “employ targeted and strategic tariffs.” New U.S. tariffs, and the retaliation they would provoke from others, would be extremely damaging for the trading nations of Asia.

Second, the way the next U.S. president manages relations with China is of great consequence to Indo-Pacific states. This is, after all, the most important bilateral relationship in the world.

Many are concerned that Trump would be overly combative with Beijing. Just as concerning, however, is the possibility that he would be attracted to the idea of a grand bargain with China, perhaps trading away the security interests of the United States and its Indo-Pacific allies in return for trade concessions. This is, after all, the man who fêted Xi Jinping at Mar-a-Lago with “the most beautiful piece of chocolate cake.”

Harris would inherit from President Joe Biden a balanced policy of competing and cooperating with Beijing. But the Biden administration has been unusually focused on Asia. Typically, Democratic administrations have paid more attention to transatlantic relations than transpacific ones. It is hard to predict what kind of Asia policy a President Harris would adopt.

Finally, the two candidates would approach the United States’ Asian allies differently. Last time around, Trump treated allies not as friends, but as freeloaders. In fact, both China and Russia would dearly love to have alliance networks as powerful and cost-effective as those of the United States. Trump’s plans to “make America great again” neglect a fundamental pillar of American greatness: its system of global alliances.

President Biden has taken an allies-first approach to Asia. The administration has brought Japan and South Korea closer together, quickened the United States’ connections with India and Vietnam, stood up AUKUS (the trilateral security agreement among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States), and convened both the Quad (Australia, India, Japan and the United States) and the Squad (Australia, Japan, the Philippines, and the United States).

As Biden’s vice president, Harris has visited four of Washington’s five Asian treaty allies—Japan, the Philippines, South Korea and Thailand—with Australia being the exception. Questions remain on what she would she do as president and how she would further strengthen Washington’s relations with its allies and the relations between them.

Based on the two candidates’ worldviews and their likely approaches to China and to U.S. alliances, officials in most allied Indo-Pacific capitals would like Kamala Harris to beat Donald Trump in November. Of course, allies don’t get a vote.

Indo-Pacific Region Braces for Change, Opportunity With New U.S. Administration

The United States remains the world’s preeminent military power and largest economy. It is natural that the outcome of its presidential election will have global consequences, including for the Indo-Pacific. To some degree, there is a growing bipartisan consensus around China’s emergence as a peer competitor of the United States, but the details in policy approach between potential Republican and Democratic administrations after 2025 still matter in at least two ways.

The first is what a second Donald Trump or first Kamala Harris administration could mean for the United States’ security posture. This has implications for the kind of burden-sharing arrangements the United States will work out with allies such as Australia, Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea, and with partners such as India, Singapore, and Taiwan. Moreover, how will the next president harness the United States’ considerable military budget to counter China’s massive naval and rocket forces buildups in the western Pacific?

The second involves the implications for the United States’ economic engagement in the region. While formal trade agreements are effectively out of the question (due to a now bipartisan political consensus in the United States that Washington should not further increase market access in the region), there are a whole range of supply chain, technological security, and investment partnerships that are well within the realm of possibility. These could potentially shore up economic relations with friendly countries while building supply chain resilience in the face of a hostile China.

Trump’s economic advisors have pledged to be more liberal in their use of tariffs, but it remains to be seen how much those tariffs will be applied against friendly countries such as India, South Korea, and Vietnam, or if they would be targeted in a systematic manner against China’s overcapacity. Among developed economies, such as the United States and European Union, concerns about China’s overcapacity extend to electric vehicle batteries, legacy semiconductors, and solar energy supply chains. For Democrats, the degree to which the democracy and human rights agenda will feature in its Indo-Pacific engagement—given competing priorities—is also an open question.

For those reasons, the U.S. elections will likely be watched carefully in capitals across the Indo-Pacific, despite a considerable degree of commonality in the Republican and Democratic approaches to the region—as on Taiwan, the Quad, AUKUS, and the U.S.-Japan-South Korea trilateral partnership .